June 11, 1963: Kennedy Emerges on Civil Rights

After dragging his feet for two years, the president gave an eloquent speech

[This piece was first published in JFK Facts on June 10, 2020]

President Kennedy's growth as a leader in June 1963 is a key to understanding his life and death.

As Arms Control Today documented last year, JFK's June 10 speech at American University would influence the arms control vision all of the U.S. presidents who followed him. And as this New York Times column notes, his often-overlooked nationally televised address on June 11, 1963, signaled his evolution as a civil rights leader.

Kennedy announced that the two black students had been enrolled at the University of Alabama, overcoming the objections of racist Gov. George Wallace, and he announced that after more than two years in office and two years of violent segregationist backlash in the South, he was introducing comprehensive civil rights legislation. In an evening, JFK went from timid and calculating on civil rights issues to bold and visionary.

"We are confronted primarily with a moral issue,” he declared. “It is as old as the Scriptures and is as clear as the American Constitution."

Speaking during the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation — an anniversary he had assiduously avoided commemorating, earlier that year — Kennedy eloquently linked the fate of African-American citizenship to the larger question of national identity and freedom. America, “for all its hopes and all its boasts,” observed Kennedy, “will not be fully free until all its citizens are free.

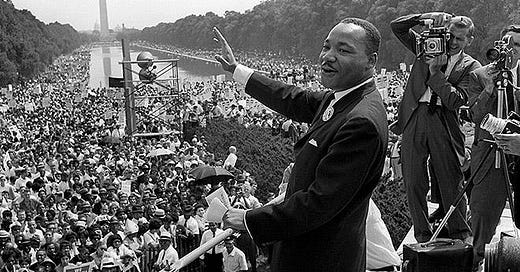

The opposition would prove violent. Medgar Evers, the Mississippi field secretary for the NAACP, was murdered by white supremacists that night, and the news would overshadow Kennedy's speech. The Southern congressmen who dominated Congress disdained the civil rights proposal and Martin Luther King began to organize a march on Washington to rally support.

A powerful, timely, and moving speech. Long overdue not just by President Kennedy, but by all American presidents since Lincoln.

The fact that it was given the day after President Kennedy’s speech at American University is a poignant reminder of Kennedy’s strengths and potential as a great leader.

And all that America and the world lost just five months later.

James Douglass writes persuasively of the dramatically expanding influence of JFK's spirituality on the conduct of his professional duties.

Such growth clearly is beyond the capacities of the vast majorities of historians, biographers, and journalists to perceive, let alone comprehend. They view their subjects as rigidly programmed automatons with totalities precisely reflecting the sums of their parts.

Let's not fear to recognize the metamorphosis that JFK underwent near the end of his life for what it clearly was: enlightenment of the most profound order -- an irresistible burgeoning of a conscience that was energized by Lasky at the London School of Economics and manifested as anti-imperialism during his early years in Congress.