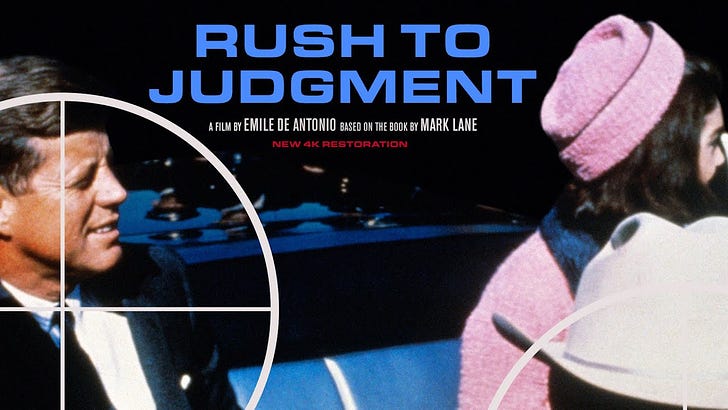

‘Rush to Judgment’ Ready to Provoke Once Again

The seminal JFK assassination documentary is re-released in conjunction with 60th anniversary of president’s death

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to JFK Facts to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.